Tyrannosaurs' Long Legs May Have Been for Marathons, Not Sprints

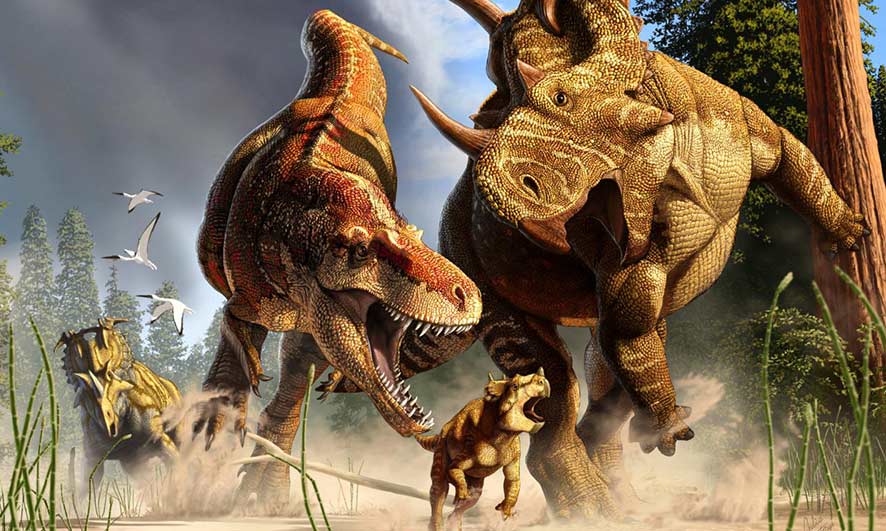

A Daspletosaurus (a relative of T. rex) hunts a Spinops (a relative of Triceratops).

Julius Csotonyi, 2020

CC BY: Redistribution permitted with credit

(Inside Science) -- Giant predatory dinosaurs such as T. rex likely evolved long legs not so much to chase prey as to spend hours on the prowl, a new study finds.

Tyrannosaurs and other theropods were the largest predators known to have ever lived on land. Previous research on these bipedal reptiles found that long legs helped them run faster, but Alexander Dececchi, a paleobiologist at Mount Marty College in Yankton, South Dakota, wanted to see if lengthy limbs might also have had benefits at slower paces.

"We always like to hear about the fastest and strongest and other superlatives, but what we have to remember is that the last burst of speed when, say, a lion is going after a zebra is only a very small part of the day of an animal," Dececchi said. "Wolves and other predators hunt for hours, wandering, foraging around for food."

The scientists analyzed the limbs, gaits and masses of more than 70 species of theropods, ranging in size from about half a pound to more than 9 tons. They estimated the dinosaurs' top speeds as well as how much energy they expended while walking at a more relaxed pace.

The researchers found that among smaller to medium-sized species, longer legs did likely boost running speeds, helping them to catch prey and escape predators. However, for giant theropods weighing a ton or more, body size limited top running speeds, so large species with longer legs ran no faster than those with stubbier limbs.

Still, longer legs did convey a benefit to giant theropods -- they made walking more efficient. "Once you get bigger than a ton, you're the equivalent of the top grizzly bear in the area, so you're basically high enough in the food chain where you're not worried about anyone else eating you," Dececchi said. "So saving energy becomes more important. At that size, you switch over from a sprinter to a marathoner."

The cruising speeds of these giant theropods "were still relatively fast compared to people," Dececchi said. "A slow T. rex walk would be, say, 4 miles per hour, which is a jog for most people."

Future research will explore how such efficiency might have impacted the ecosystems of these giant predators. If an animal saves hundreds of calories a day by walking efficiently, it won't have to make as many kills, Dececchi said. "That's of huge benefit to you as a T. rex in lean times, and it also means an area could support more T. rexes."

The scientists detailed their findings online May 13 in the journal PLOS ONE.