Largest Known Maya Structure Found, More than 4,000 Feet Long and Nearly 3,000 Years Old

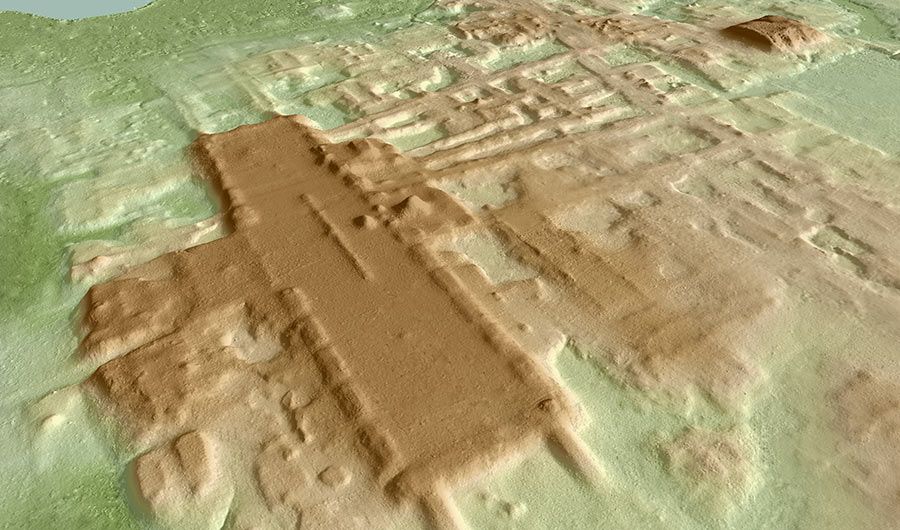

3D image of the recently recognized Maya site of Aguada Fenix, based on lidar.

Takeshi Inomata

May be used with this Inside Science story, with credit given.

(Inside Science) -- A giant platform nearly a mile long made of stone, clay and earth is both the earliest and largest known monumental structure constructed by the ancient Maya, dwarfing their biggest pyramids in magnitude, a new study finds.

The people known as the ancient Maya lived in an area the size of Texas across what is now southern Mexico and northern Central America, including the modern countries of Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. At its height, known as its Classic period, which spanned from roughly A.D. 250 to 900, the Maya arguably had the most advanced civilization in the Americas, raising cities known for their stone pyramids.

Archaeologists long thought the Maya gradually shifted from a mobile way of life to permanent settlements during the Preclassic period that spanned from roughly 1800 B.C. to A.D. 250, emerging with villages during the Middle Preclassic from 1000 to 400 B.C. However, the discovery of major cities built during the Preclassic challenge this model. For example, the La Danta pyramid complex in the Preclassic city El Mirador rises 72 meters high with a base 500 meters by 300 meters large, dwarfing any Maya pyramids of later periods.

Now scientists have discovered the largest known ancient Maya ceremonial structure, a platform roughly 1.4 kilometers long, 400 meters wide and 10 to 15 meters high. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples from the platform revealed it was constructed between 1000 and 800 B.C., which also makes it the oldest known ancient Maya ceremonial structure.

The site lies partly on Rancho Fénix (Phoenix Ranch) in Tabasco, Mexico. Since artificial reservoirs, called aguadas, are prominent features of the area, the researchers named the site Aguada Fénix.

The scientists discovered the site using an airborne laser scanning technique known as lidar to create a 3D map of the surface below. Maya ruins are often hidden by jungle, but this site was largely deforested. "It is surprising that this site was not known before, but it is so large horizontally that if you walk there, you do not realize that it is a human construction and never recognize its rectangular shape," said study lead author Takeshi Inomata, an archaeologist at the University of Arizona at Tucson. "Its form became clear through lidar."

All in all, the researchers estimated this platform took 3.2 million to 4.3 million cubic meters of material to create. In contrast, the La Danta pyramid required only about 2.8 million cubic meters of material. (In comparison, the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt has a volume of only 2.3 million cubic meters.)

Aguada Fénix becomes more impressive once its surroundings are considered, including nine causeways radiating from the platform built at roughly the same time, with the longest of these stretching 6.3 kilometers. These causeways suggest the giant platform "is just the central precinct of a very, very, very large place," said Thomas Guderjan, president of the Maya Research Program, who did not take part in this research. "The scale of it is enormous."

The platform "was probably used for rituals involving lots of people," Inomata said. These may have involved processions of many people who gathered from surrounding areas, as well as artifacts such as jade axes the researchers found at the site.

One possibility is that the platform might have served as a marketplace, Guderjan said.

After roughly 800 B.C., Aguada Fénix and most other nearby sites were abandoned. As maize became increasingly important, people may have moved to higher, better-drained terrains, he said, avoiding wetter, mosquito-ridden areas.

Aguada Fénix lies at the western edge of the Maya lowlands. The researchers originally investigated the site to look for clues concerning the relationship between the Maya and the Olmecs, the earliest known major Central American civilization. Archaeologists have often debated whether the Olmecs were a "mother culture" from which the Maya originated, but the age and complexity of Aguada Fénix suggests the Olmecs did not give rise to the Maya, Guderjan said.

Guderjan noted the sheer number of Classic buildings still greatly outweigh Preclassic ones. Although Preclassic Maya likely had larger population centers than previously thought, Classic Maya may have reached a population density rivaling that of medieval Europe, Guderjan added.

The only sculpture found so far at Aguada Fénix apparently depicts a white-lipped peccary. Unlike some other archaeological sites from around the same period, Aguada Fénix lacks sculptures of kings or other social elites, the researchers said. This may suggest Aguada Fénix displayed less social inequality than Olmec sites of the same era or later Maya sites.

Still, Guderjan noted, "I'm not sure the absence of monuments celebrating kings necessarily means there was less social inequality here. There are lots of places that have a lot of social inequality that don't have statues of rulers sitting around."

In the future, Inomata and his colleagues want to learn more about how the people at this site transitioned from a mobile lifestyle relying mostly on hunting and fishing to more sedentary life dependent on maize agriculture. "But finding residential areas of mobile people is a challenge, particularly in the tropical area," he said.

Other giant platforms from the ancient Maya likely await discovery, Inomata added. "Archaeologists have focused on pyramids and other tall buildings, and have not realized the enormity of those platforms," he said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the June 4 issue of the journal Nature.