What If Ernest Hemingway Wrote the Bible?

(Inside Science) -- Algorithms that computers use to translate something written in one language into another are easy to find. Some even work.

But every writer has a unique style -- what writers call voice -- that identifies them and distinguishes them from other writers. Getting computers to take the words of one author's style and convert them into another's style while leaving the meaning intact is much harder.

Style translation algorithms could be used to render texts readable that normally are not, like a program that translates a legal document into lay language or makes a work of English literature understandable to someone who is learning English as a second language or is too young to understand many of the words.

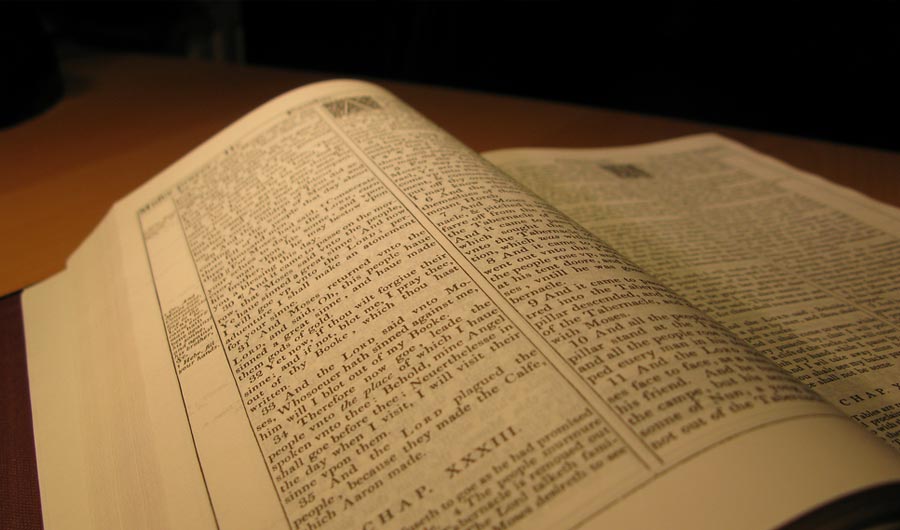

A small group of computer scientists at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire, and Indiana University in Bloomington has taken a step toward producing such an algorithm, using various editions of the Bible. They used 34 English language versions of the New and Old Testaments to train and test the system.

The Old Testament originally was written in Classic Hebrew, with some portions in Aramaic. The New Testament was originally written in Greek. Some translations reflect the time period when they were produced, so the King James Version, first published in England in 1611, is full of "thees" and "thous," and modern ones are not.

"The goal was to see if we could basically use the translation framework to do some form of style translation," said Dan Rockmore, a professor of mathematics and computer science at Dartmouth.

The researchers chose the Bible for the study because it is perhaps the most annotated and indexed literary text in existence. It comprises 31,000 verses and enabled the construction of 1.5 million unique pairings of words from one version with words from other versions, which provided data needed for training the system. For instance, Genesis 1:1 in one Bible translation matches Gen. 1:1 in all the others.

However, using the Bible as the texts -- or corpus -- with which to train and test the system may be a weakness in the study, said Shlomo Argamon, a forensic linguist and computer scientist at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. It has multiple styles, sometimes within one book.

"You have the prophetic books, some of which are full of very high poetry, and stories about marrying prostitutes. You have Proverbs, which itself has multiple styles," he said.

"We treat every version of the Bible as a single style for our work," said Keith Carlson, a computer science doctoral student at Dartmouth who worked on the project.

To train the algorithm, the Dartmouth and Indiana researchers used a definition of style that included such characteristics as sentence length, the use of the passive or active voices, and vocabulary.

The experiment is a proof of concept, said Rockmore. The research is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Besides altering style for the audience, another long-range goal, said Rockmore, is for the algorithm to be able to learn the style of one author, and translate it into the style of another author as a test of agility. That is not easy, and the Dartmouth algorithm can’t do it yet.

Readers generally ignore or don't notice a particular writer's style since in many cases it is not very strong, or writers learn to control it when necessary.

Trying to identify an author by style is more difficult than one can imagine, Argamon said. It would be possible to run Herman Melville's novel "Moby Dick" through an algorithm designed to identify individual writers' styles and erroneously conclude the novel had two authors, he said, because there seems to be two styles.

Ernest Hemingway, however, might be easier. He was noted (some might say notorious) for his unique and obvious writing style.

The writer Joan Didion, who also had a style of her own, dissected the famous opening paragraph of Hemingway’s masterpiece, "A Farewell to Arms," for the New Yorker in 1998.

She noted the paragraph had four simple sentences, 126 words. Only one word had three syllables, 22 had two, all the rest, one. Twenty-four of the words were “the,” 15 “and.” There were only seven adjectives. And each word was placed deliberately to create a rhythm.

That is information a computer algorithm could use to recreate Hemingway’s style, if it were trained to do so. The new algorithm can't do that yet, but at Inside Science’s request, the researchers asked it to do the reverse: They fed some Hemingway into the computer and changed the style to various editions of the Bible. The changes were subtle.

In Hemingway's novel "For Whom the Bell Tolls," a man describes how he was so much in love with a woman he just met, it is as if he had known her all his life.

HEMINGWAY: "I love you when I saw you today and I loved you always but I never saw you before."

1599 GENEVA BIBLE: "I have loved thee, when I have seen thee this day, and have loved thee always, and have not seen thee before."

INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S BIBLE: "I loved you when I saw you today. I loved you always, but I did not see you before."

Argamon, a forensic linguist known for his work on computational stylistics, said he would find the corpus of Bible texts the Dartmouth and Indiana researchers created useful in his research, but was critical that the researchers treated the corpus as undifferentiated data -- typical of computer scientists, he said -- and not as words with context, a weakness linguists (and English majors) would understand.

There is, he said, more to the words than just the words.